The Bible as it has come down to us preserves a number of varying traditions concerning the size and border of the promised land. Said differently, throughout the roughly six centuries that defined the monarchy, Israel’s exile, and its post-exilic restoration, biblical scribes variously delimited Israel’s borders, often in idealized and utopian ways. This fact the biblical record bears witness to.

And Yahweh spoke to Moses: “This is the land that will fall to you as an inheritance, the land of Canaan by its borders” (Num 34:1-2).

Numbers 34 is generally attributed to the Priestly source. As such, and despite the rhetorical/literary technique of presenting what follows as the word of Yahweh, it outlines the borders of the promised land as they were envisioned by this 6th-5th century priestly guild. Yet when studied comparatively with other textual traditions from the Bible, we notice some glaring differences. And these differences or contradictions should be understood in light of the fact that different scribes and geopolitical time periods envisioned the borders of the promised land differently. For ease of viewing these differences, I address each of Israel’s borders separately.

Variant Traditions concerning Israel’s Southern Border

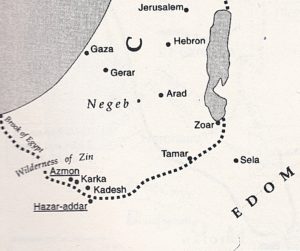

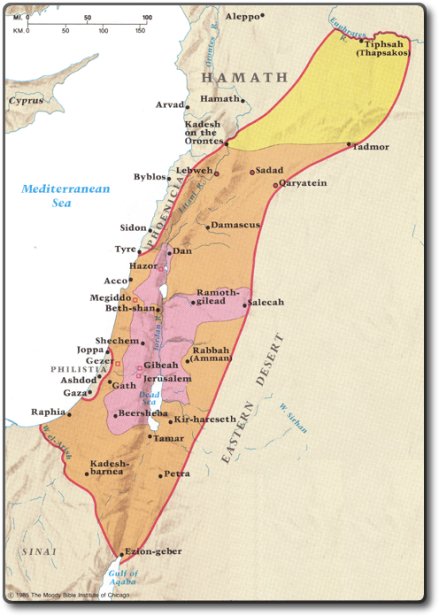

1. According to the priestly guild responsible for writing Numbers 34:3-5, the southern border of the promised land extends in a curved line through the wilderness of Zin from the bottom of the Dead Sea adjoining Edom, around Kadesh, and then toward the Mediterranean through the Wadi of Egypt.

Roughly speaking this is the same southern border expressed in Joshua 15:1-5 and Ezekiel 47:19, and can be made to align with the more general references of “the wilderness” or “the Wadi of Egypt” as Israel’s southern border as found in Gen 15:18, Deut 1:7-8, and Josh 1:4.

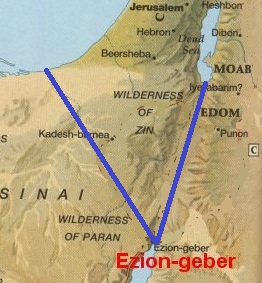

2. But the southern border delimited in Exodus 23:31 is acknowledged to be much larger: “from the Red Sea to the sea of the Philistines.” In other words, the eastern border extends straight down from the bottom of the Dead Sea until Ezion-Geber on the Red Sea. In Exodus 23:31, then, the southern border is conceived of as a line from Ezion-Geber on the Red Sea (or literally the sea of Reeds) to the Mediterranean.

This extended southern border into the land of Edom can only be accounted for by acknowledging Israel’s expansion into Edomite territory under Solomon’s reign (e.g., 1 Kgs 9:26)

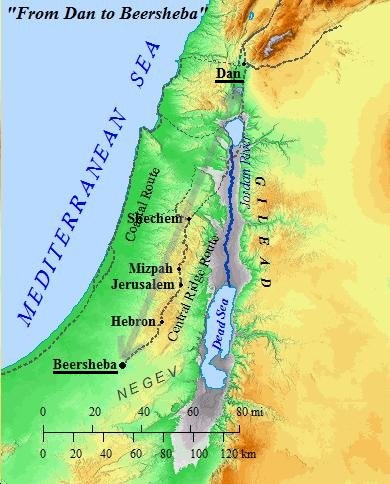

3. Yet another biblical tradition acknowledges Beersheba as the southernmost tip of the promised land. The phrase “from Dan to Beersheba” is found 9 times in the Bible, most prominently in the books of Samuel: “And all Israel from Dan to Beersheba. . .”

This expression which first appears at the end of Judges (20:1) sharply contradicts the borders of the land in the conquest narratives of Joshua (#1 above). I will return to this expression when discussing the variant traditions concerning Israel’s northern border.

Variant Traditions concerning Israel’s Western Border

Roughly speaking, there are no variant traditions concerning Israel’s western border. That is, the Bible’s various traditions either reference the Mediterranean sea as its western border (e.g., Ex 23:31; Num 34:6; Deut 11:24; Josh 1:4; Ezek 47:20) or are silent on the matter (e.g., Gen 15:18).

That’s not to say that the assigning of the Mediterranean sea as Israel’s western border did not pose problems for the biblical scribes. Most scribes for example seemed to be cognizant of the fact that historically speaking the southwestern coastal region occupied by the Philistines and northwestern coastal region occupied by the Phoenicians were never controlled by the Israelites, only briefly during David’s unified monarchy (2 Sam 8:1-2).

But in general these coastal regions historically remained outside of Israel’s borders.

Noteworthy also is that the book of Joshua’s portrayal of the allotment of the land (Josh 13-19) acknowledges that the Philistine coastal region, although allotted, remained to be conquered (Josh 13:2-4), as well as the northwestern coastal region occupied by the Phoenicians, where the northern borders of Asher and Naphtali stopped.

Yet in stark contrast to this tradition, the text of Joshua 21:41-43—apparently part of the same tradition—presents Yahweh claiming that the Israelites took possession of “the whole country which he [Yahweh] had sworn to their fathers that he would assign to them. . . Everything was fulfilled!” Thus according to this “fulfilled” prophetic announcement, the promised land as Yahweh swore to the patriarchs is very much represented in the map above—that is without the coastal regions of the Philistines and the Phoenicians!

Finally, if biblical scribes were cognizant of the fact that Israel never occupied these coastal regions why then did they conceive of the promised land as encompassing these regions? Scholars have long noted that biblical scribes, and especially the later 6th century traditions of Numbers 34 and Ezekiel 47 did not acknowledge the southwestern coastal region occupied by the Philistines and northwestern coastal region occupied by the Phoenicians because they were working from a map of Canaan that was used by the Egyptians prior to the arrival of these sea peoples, when Canaan was merely a providence of the Egyptian empire during the 15th-11th centuries (see below).

Variant Traditions concerning Israel’s Northern Border

Biblical traditions on Israel’s northern and eastern borders display the most variation. Here are the traditions on its northern border starting from the most expansive claims.

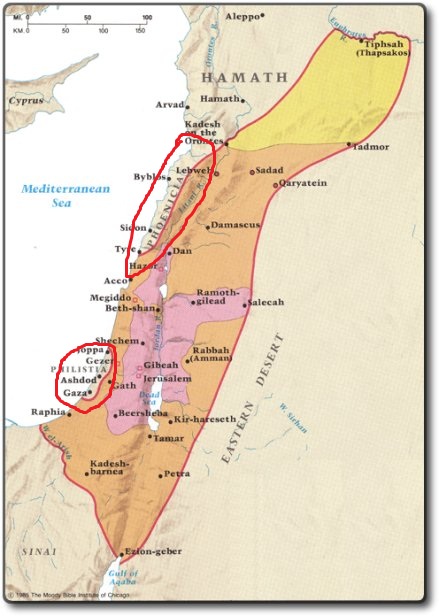

1. Gen 15:18, Ex 23:31, Deut 1:7 & 11:24, and Josh 1:4 all reference the Euphrates as Israel’s northeastern border, usually articulated as “from the wilderness to the Great river.” This is allegedly the extent of David’s conquests and unification of Israel.

2. Yet the traditions preserved in Num 34:7-9, Ezek 47:15-17, and 1 Kings 8:65 speak of Lebo-Hamath in Lebanon as the northern border of the land that Yahweh promised to the patriarchs. And this is also reflected in Joshua 13-19 as the land allotted, but not yet conquered (Josh 13:2-6).

This northern border not only reflects an idealized vision of the promised land used by both the post-exilic authors of Numbers 34 and Ezekiel 47, but these borders, including the Philistine and Phoenician coastal regions, also express the borders of Canaan as they were attested when it was an Egyptian province (cf. 2 Kgs 24:7).

3. And finally, “From Dan to Beersheba.” This expression is used approximately 9 times in the Bible, often from the books of Samuel (1 Sam 3:20; 2 Sam 3:10, 17:11, 24:2, etc.), and roughly delimits the land allotted to the Israelites in Joshua 15-21 (see above). Again, this tradition which acknowledges the northern boundary as set by Dan and Sidon on the west coast (Josh 19:28) contradicts the traditions of Numbers 34 and Ezekiel 47 which acknowledge the northern boundary at Lebo-Hamath, and the traditions listed in #1 which acknowledge the river Euphrates as the northern boundary.

It must be noted also that although Joshua 13:5 presents Yahweh claiming that “the whole valley of Lebanon from Baal-gad at the foot of Mount Hermon to Lebo-Hamath” remained to be dispossessed (although already allotted), the historical reality is that the Israelites only conquered this area for a limited time under Solomon, and more so it seems to contradict the conclusion of this very tradition itself (Josh 15-21) which states that “Yahweh gave Israel the whole country which he had sworn to their fathers. . . not one of the good things which Yahweh had promised to the house of Israel was lacking. Everything was fulfilled” (Josh 21:41-43). This tacitly acknowledges that Israel’s northern border extended to Dan, period.

Variant Traditions concerning Israel’s Eastern Border

The main variant in the biblical traditions that speak of Israel’s eastern border was whether or not scribes understood Gilead and Transjordan as part of the promised land or not.

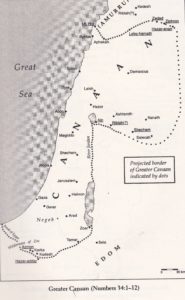

1. The tradition preserved in Numbers 34:1-12 ends by delimiting the eastern border “from Hazar-Enan to Shepham” and then from Shepham to the Sea of Chinnereth, that is Galilee. Then we are informed that from the Sea of Galilee “the border shall descend along the Jordan, with it concluding at the Dead Sea. This shall be your land, delimited by its surrounding borders.” This is reproduced in the map immediately above.

So according to this tradition, which comes from the Priestly source, the Transjordanian allotment is not included in the borders of the promised land, the land of Canaan proper.

It is no coincidence that the borders of the promised land in Numbers 34:1-12 are nearly identical with those envisioned in Ezekiel 47:13-20, whose text can more securely be identified with a utopian vision of the borders of Israel during the post-exilic period. Scholars have continuously noted numerous theological and linguistic parallels between the Priestly source of the Torah (here Num 34) written by Aaronid priests of the exilic to post-exilic periods and the Zadokite Aaronid author of the post-exilic text of Ezekiel. This is just another in a long list of parallels.

But where did this idealized map of the promised land of Canaan come from? Apparently, these were the same borders that the Egyptians used to delimit the province of Canaan when it was under their hegemony during the 15th to 11th centuries BCE. So our priestly authors draw from the past to define the land of Canaan as it was delimited by the ancient Egyptians at the time prior to the invasion of the Sea peoples and occupation of the coastal regions (see above).

2. In Deut 34:1-4 our scribe claims that “the land that Yahweh swore to Abraham” included Gilead. But this Transjordanian territory is not considered part of the promised land according to the post-exilic traditions of Numbers 34 and Ezekiel 47. Indeed according to the Priestly tradition (see Num 26 & 32) it was considered a settlement outside of the promised land.

In comparison to other biblical traditions, the Deuteronomic tradition takes a unique position here—namely that the Transjordanian settlements were a part of the promised land. This view, contrary to the Priestly tradition, comes through in a number of features unique to the Deuteronomic tradition. For instance:

- In its renarrations of the Transjordanian conquest stories, Deuteronomy 1-3 has Yahweh proclaim that the possession of the promised land starts in Transjordan as soon as the Israelites cross the Wadi Arnon—“Come and possess the land that Yahweh swore to your fathers…” (1:8)—and not the crossing of the Jordan as typically conceived in other traditions. That is, the Israelites are to start their possession in Transjordan!

- In its retelling of the conquest of these Transjordanian territories, the Deuteronomist adds a uniquely Deuteronomistic ideological program to the conquest narrative—the herem. This was a religious ban that dictated that all conquered peoples and objects be sacrificially offered up to Yahweh in complete and utter destruction (see Contradiction #324 & #342). We will look at the specific contradictions between the Deuteronomist’s version of these conquest narratives and those of the earlier Yahwist source in forthcoming posts. Here we merely note that the Deuteronomist added this to his vision and version of these conquest stories to state as it were that these Transjordanian territories had been purified of all non-Israelite practices through the herem.

- The Deuteronomist’s herem ideology goes hand-in-hand with this tradition’s perception of the Transjordanian land as pure. See also the Deuteronomist’s application of this same herem ban in his laws governing the conquest of the land of Canaan in Deut 7. It’s an expiation and purification of the land, which was necessitated in the Deuteronomic tradition because the Deuteronomist viewed Transjordan as part of the promised land. Compare this to the Priestly editor’s views that these Transjordanian territories were, on the contrary, “unclean” in the story of Reuben and Gad’s altar in Joshua 22:11-34.

- Finally, the Transjordanian territories were given unconditionally to the tribes of Reuben and Gad and the half tribe of Manaaseh according to the Deuteronomic tradition that viewed this land as part of the allotted territory of the promised land. Not so for the Priestly tradition’s retelling of this tradition in Numbers 32 where the land was granted to the tribes of Reuben and Gad on condition that they cross over and help the rest of Israel conquer the land of Canaan. See Contradiction #323.

3. Finally, as we saw above, Ex 23:31 proposed an extended eastern border that reached into the southern territory of Edom all the way to Ezion-Geber on the Red Sea.

This begs the question of what the borders of pre-exilic Israel and Judah actually were. As I recall Israel Finkelstein believes that based on the locales associated with Saul, Saul’s territory did not extend as far north as the Jezreel valley. I have also read that the territory described as belonging to the tribe of Asher doesn’t really make any sense, as it’s mostly disconnected villages (and Solomon ends up gifting that territory to Hiram of Tyre in any case).

Robert, all good points. You’re probably more conversant in this than I am. I am familiar with the fact that these borders were idealistic and utopian in nature—as may have been the whole narrative on David’s conquests and Solomon’s kingdom. However it’s been a while since I’ve read up on what the real historic borders may have been in the early monarchy. I’d have to go back and do some reading myself in this area.

Can someone do an overlay of the largest description of Israel’s borders with the current borders for Israel? It would be good to have a visual of the potenially largest region to what it is now. Please email when an overlay is available.

I find it very sad that you start out from the assumption that there are contradictions in the Bible, based – at least in this case – on the utterly discredited documentary hypothesis, on which no two scholars agree, and which breaks up the text into random portions. Far better to take the Pentateuch as a unity to see the development of God’s working with his people Israel. The Numbers 34 description of the promised land makes so much more sense if seen as the ‘map’ given to Moses before the people entered, than some scholarly theory that it was cobbled together by unknown scribes centuries later for some ideological reason. You may well find that a lot of the alleged ‘difficulties’ disappear when scholarly assumptions are removed from them.