Everyone knows that when the Israelites asked for food and water from the Edomites, the Israelites’ brothers from the line of Esau, and permission to pass through their country they were denied these things and forced to pass around Edom. This story we know from Numbers 20:14-21, which scholars have identified as part of the older southern Yahwist tradition [J].

Yet when Moses renarrates this story some 40 years later, narratively speaking, this is what he says of the event.

And we turned and traveled into the wilderness by way of the Red Sea as Yahweh spoke to me, and we skirted Mount Seir for many days.

Then Yahweh said to me: “You have skirted this mountain long enough. Turn north, and command the people saying, ‘You are to pass through the territory of your brothers, the children of Esau, who live in Seir. And they will be afraid of you, so be very watchful. Do not agitate them, for I will not give you any of their land, even as much as a footstep, because I have given Mount Seir to Esau as a possession. Food you shall buy from them with money so that you may eat; and water also, you shall buy with money so that you may drink. For Yahweh your God has blessed you in all the works of your hand. He has known your walking through this great wilderness. These 40 years Yahweh your God has been with you; you have lacked nothing.’

So we passed through among our brethren, the children of Esau, who live in Seir. (Deut 2:1-8)

Besides the obvious differences in terminology that Moses uses here when speaking of Edom—the Mount Seir region and “the children of Esau who live in Seir”—it’s clear that Moses has once again significantly altered the details of this event/story in his renarration of it. (See Moses Retells his Story Part I & Part II). We must ask, therefore, on what grounds were these changes being made? Why did “Moses” even alter these details in the first place? And how could he?

As with the last episode (see Moses Retells his Story Part II and Contradictions #357-363), here too Moses claims that Yahweh said certain things to him which he was then to relay to the people. But in the “original account” in Numbers 20:14-21 not only did Yahweh not say the things that Moses here accredits him with saying, but the outcome of the whole affair was completely contradictory to what Moses here claims Yahweh says as a sort of prophetic pronouncement: “You will pass through the territory of your brothers”; “they will be afraid of you;” and “you will purchase food and water from them.” None of these things happened! Not one of them. The Israelites did not procure food and water from their brethren, nor did they pass through their land. Instead the children of Esau, who were anything but afraid, marched out “with a heavy mass of people and a strong arm” (Num 21:20-21) and it was rather the Israelites who were afraid and forced to flee for fear of their lives!

Furthermore, in Moses’ renarration he claims that after having passed through the territory of their brethren they then marched through Moab (Deut 2:18-29). But again this is contradictory to the original record where the Israelites then turn back to Kadesh, and then proceed to Hor and Hormah, and then around Moab not through it (but see my Intro to Numbers 21 and Contradiction #268, #274, #275, #279, and #281)! Why did Moses renarrate this history in radically opposing terms to its original record? How could he blatantly contradict the historical record? And upon whose authority were these alterations being made?

These questions, and what they frustratingly imply about Moses and Scripture, might easily be those of a Christian fundamentalist as he grapples with the narrative discrepancies between these two accounts. Yet as we shall see, these questions themselves have been erroneously shaped by later beliefs that most Christian fundamentalist hold about the Bible. So here “Moses'” altered retelling and blatantly contradictory claims have nothing to do with an historical Moses (if indeed he existed) nor with an historical event that allegedly transpired in the mid 15th-13th century BCE (see Contradiction #81). Rather this is how a later scribe—let’s call him the Deuteronomist [D]—used the character of Moses as an authoritative mouthpiece so that he could legitimate a new retlling of this story that suited the needs and concerns of his own historical audience and geopolitical worldview (see my Introduction to Deuteronomy and Contradiction #349 for more clarity on this). So let’s look at exactly how this has happened and why.

One of the first things we notice in the Deuteronomist’s renarration is the emphasis placed on calling the Edomites “brethren.” This minor detail gives us a glimpse into the perspective of our author, and it is one of sympathetic brotherhood towards the Edomites. This same perspective is presented in two other places in the book of Deuteronomy as well:

- In Deut 2:22 our author, again contrary to another earlier tradition (see Contradiction #68) claims that Yahweh also aided Edom in dispossessing its original inhabitants, the Horites.

- Unlike the descendants of Moab and Ammon who can never enter into Yahweh’s community (Deut 23: 1-5), a third generation Edomite can, specifically because he did come out with food and water! “You shall not abhor an Edomite because he is your brother” (Deut 23:8-9).

Not every historical period during the monarchy supported such a brotherly view toward Edom. Most of the time the Israelites viewed the Edomites with bitter hostility. In other words our author’s perspective towards the Edomites is a clue to the historical context of this retelling, its Sitz im Leben, which is utterly contradictory to the hostile relationship depicted in the earlier narrative of Numbers 20.

We might also tentatively note that the hostility expressed between Israel and Edom in the Numbers 20 version [J] might have been used to explain why Israel and Edom had a hostile relationship during the historical time period in which this version was written, most likely during the early monarchy. Likewise, the brotherly and cooperative relationship between Israel and Edom expressed in Deuteronomy’s version might have been used to explain why Israel was more brotherly toward Edom during the historical period in which this retelling was told. The historical record hasn’t changed; this has nothing to do with presenting a more veritable account. Rather the geopolitical realities and perspectives that separate these two accounts have changed and that change has caused our storytellers to recite this ancient story in radically different terms.

So here we get our first lesson in what historiography was and was used for in ancient times—to express the whys and hows of ever-changing geopolitical realities. If in a later period Israel and Edom saw themselves as more brotherly, then one could understand why and how a later scribe might have retold this archaic story to express his geopolitical reality. Indeed, this is exactly what the Bible’s stories are and did indeed express—current geopolitical realities and relationships. In other words these archaisized stories of the past tell us more about their author’s own historical time period than they do about any alleged confrontation in a distant archaic past!

Another notable difference in the Deuteronomist’s retelling is the lack of mention of a king of Edom, and more significantly of an independent state called Edom! So we move from the older J narrative that recognizes an independent state called Edom and its king—again expressing early monarchical geopolitical realities—to a text that makes no explicit claims on these matters but rather now speaks of a people, “the children of Esau, (not a state) and a geographical area, Mount Seir, (not a kingdom or statehood)! So naturally we ask: under what historical period is this geopolitical perspective most valid?

Our knowledge of Edom is sketchy at best, and most of our references from the ancient world come from biblical scribes. It is clear that the older J source (Num 20:14-21) represents tensions between Israel and Edom during the early monarchy, where Edom is reported to have a king even when it was a vassal state of Judah (mid 9th c.). We also know that the state of Edom ceased to exist somewhere in the 6th century when it was destroyed by the Babylonians. But this post-exilic geopolitical reality could hardly be what is expressed in Deuteronomy 2 since by and large post-exilic scribes casted extremely vitriolic words toward Edom because of their help in destroying Judah (see the prophetic literature: Isaiah 34:1-17; Jeremiah 49:7-22; Ezekiel 25:12-14; and Obadiah). Rather it’s more probable that Deuteronomy reflects the geopolitical realities of the 7th century when Edom’s statehood was waning and when the Assyrians had pulled out of the region leaving, momentarily, the southern kingdom of Israel in a position to regain territories lost to the Assyrians themselves in the previous century. King Josiah’s attempt to rebuild the Davidic dynasty might have recognized the children of Esau’s right to the region of Mount Seir as attested in Deuteronomy 2. At any rate, the hostile image in the earlier Yahwist telling and the non-hostile and brotherly retelling of the same story by the later Deuteronomist reflect two drastically different geopolitical realities, or the perspectives on those realities.

The most significant differences—indeed blatant contradictions—between these two tellings is that in the earlier J account Israel is refused passage, refused food and water, and must fearfully flee and traverse around Edom. The Deuteronomist has his Moses radically alter these narrative elements. On a theological level, the most visible element that the Deuteronomist adds to his account is the divine command to pass through Edom, not to pick a fight with them nor take their land, and to procure food and water from them. Having Yahweh decree both the safe passage of the Israelites through Edom and their procuring of food and drink, adds a prophetic element to the narrative that is absent in the older source. In Deuteronomy, Yahweh wills this all to happen: “You will be passing through” (2:4); “You shall acquire food. . . you shall procure water” (2:6); “Indeed Yahweh your god has blessed you in all your undertakings” (2:7). On a rhetorical level, presenting Yahweh willing the safe and peaceful passage of the Israelites aids to legitimate the Deuteronomist’s subversion and falsification of how the story was previously told in his older source, by now having Yahweh narrate it in a manner that suits the Deuteronomist’s theology. For more specifics on this subversion of an earlier authoritative tradition see my Intro to Deuteronomy and Contradiction #349.

The why of the Deuteronomist’s modifications to the tradition are harder to discern. But again we see that one of his motives was to present a more cooperative and respectful relationship between Israel and Edom. Scholars have suggested that this recognition of the children of Esau’s right to the land on the part of our Israelite scribe might have worked hand-and-hand with Josiah’s effort to bring Edom back into an Israelite kingdom modeled after the Davidic monarchy. At any rate, we see—for the three-hundredth-and-sixtieth time—that biblical scribes freely altered earlier traditions. But this leads us to other questions: What did the Deuteronomist himself think he was doing in subverting these earlier tellings? Did he believe these stories were historical? If he did, how could he have so blatantly changed their details?

These questions are difficult for modern readers to grapple with because many have mistakenly assumed that the Bible’s texts were unaltered by scribes and authors, and furthermore that their narrative details were unvarying and historical across the board. The overwhelming textual data collected on this website alone clearly displays the error in this line of thinking, and forces us to ask anew: What is this corpus of literature we call the Bible? Presently we need to focus on what the Deuteronomist’s interpretive process tells us.

For starters, it seems fair to deduce that whether these stories were conceived as historical or not from the Deuteronomist’s perspective (and the same question would need to be asked of the Elohist and Yahwist), it was the story and its message that were most important—that is, the message the story’s re-telling conveyed to its audience. To return to the Israel and Edom example, if it was the intention of the Deuteronomist to promote national pride in a political environment where the Israelites were currently running military skirmishes with its neighbors, by delivering stories of the past that accomplished such a purpose—displaying a great and mighty Israel, whom all nations feared—then we might at least understand why he changes the Yahwist version of the story in order to reflect this, his current need to his current audience. We must assume that the Yahwist also practiced the same literary technique, with the exception that the message he wished to convey to his audience was different, and thus he painted an Israel-Edom relationship that explained the reasons for Israel and Edom’s hostilities during his own time period. In either case, it is apparent that biblical scribes freely altered and modified the traditional stories handed down to them in order to serve their own theological and political needs. Thus, these stories of the past actually tell us much more about their authors and their authors’ present concerns than they do about what actually happened in the past itself! The question whether they actually recount historical reality is irrelevant, even to the biblical scribes who modified and transmitted these stories! What was relevant to them, as the above example indicates, was what message these stories conveyed, and that message was furthermore shaped by the scribe himself!

Again, this very fact places the emphasis of each of Deuteronomy’s re-tellings on the meaning or message that the re-telling sought to convey—a meaning and message created by the scribe himself (see Contradiction #349, #350, #351, #352-356, #357-363, and forthcoming entries). In other words, in no account in Deuteronomy 1-11 does the scribe attempt to offer a rendering that seeks to be more historically accurate! Indeed, the evidence points to just the opposite: the Deuteronomist sought to offer a rendering that expressed better his own theological beliefs, aims, and agenda. And we often see that the biblical scribes’ own geopolitical realities and theological beliefs and concerns were retrojected into the past as elements of these very stories. So again, these stories tell us more about their authors, their beliefs, and the divergent geopolitical worlds in which they lived than any historical information from an archaic past. In fact the only solid textual data we have in front of us is that biblical scribes themselves freely and consciously rewrote these stories with, not historical accuracy in mind, but their own needs, concerns, beliefs, and political agendas in mind!

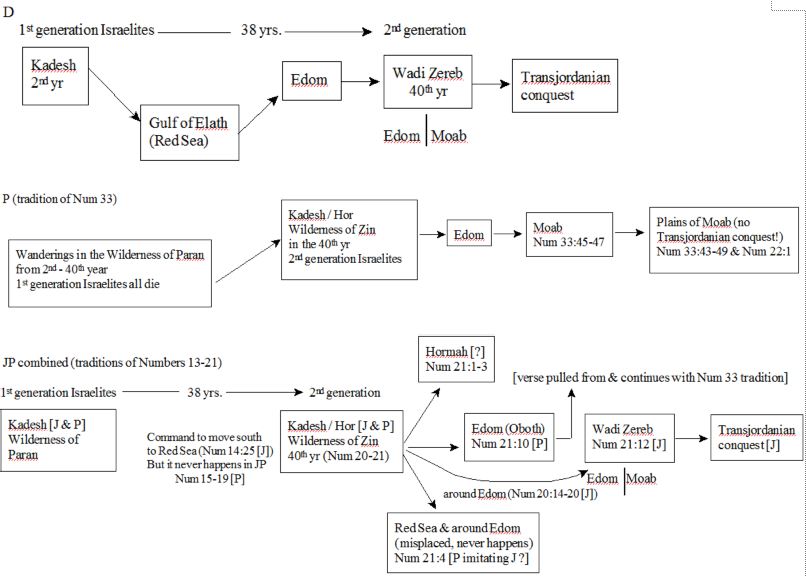

Finally, there are some large discrepancies between our sources concerning where the Israelites go after the Edom affair. I have spoken about this issue at length in contradiction #268 and will just reproduce a diagram I created that best illustrates these divergent traditions.

I’ve been thinking of what it might be like to live in a culture that only recently developed literacy. If written records only go back, say, a hundred years, what might that do to our perception of what happened before?

I don’t know what the current thinking about the cultural development of Ancient Israel, but if there were multiple traditions of a priest named Moses, and those coming from different locales contradicted with each other, might it make the people of 8th century Israel more accepting of embellishing the traditions?

On the other hand, there is also the Cecil B. DeMille movie “The Ten Commandments”. Although DeMille and most of the people involved probably believed Moses existed and did most of the things described in the movie, some of the material was obviously made up for the movie. So, the tradition was “embellished” to include an Egyptian love interest for Moses.

Hi Robert,

These are good points. I am slowly moving away from using the allegedly offensive label “contradiction” toward getting modern readers to acknowledge that Israelite scribes recited, told, and retold, and eventually wrote down their traditional stories with considerable variation. When I work through Deuteronomy, for example, and as expressed in the conclusion to the post above, it is becoming more and more clear that biblical scribes freely modified these stories so that they reflected and presented a meaning and message more in line with their own theology or geopolitical worldview. The examples I often use is a modernized version of a Shakespeare play or Dickens’ Christmas Carol.

As for the above modified retelling, I’m now led to think that what the Deuteronomist himself most wished to communicate in having his Moses renarrate this story differently was not an event in the past, but a description of how and why current relations between Israel and Edom came about, or are to be understood. Past is recited to present the present reality, or perception of it. The story defines more the current perceptions than a past historical event. Or the “past” is recited to find meaning in present geopolitical realities. And as you note, these traditions may have been more pliable because literacy was a recent phenomenon, among the elite scribes only. It’s really a story-telling world we’re talking about,