Deuteronomy 2:9-23 is another passage uniquely crafted by the Deuteronomist (see others in Contradictions #349, #350, #351, and #370) and was designed to convey themes and ideological beliefs dear to this 7th century author and his scribal guild.

Said differently, and on a textual level, despite “Moses'” insistence that after they passed through Edom—or around Edom or back toward the Red Sea or forward to Hor, depending on which tradition one reads (see Contradictions #268, #275, #364-369)—“Yahweh said to me. . .”, what follows is not found in the earlier traditions that record this event in Numbers 20-21. Rather it was created by the Deuteronomist to demonstrate a uniquely Deuteronomic theme: the rightful dispossession of indigenous peoples.

The purpose of Deuteronomy 2:9-23 is to present earlier precedents for the dispossession of indigenous peoples, thereby preparing the reader for the “rightful” dispossession of the indigenous Canaanites by the conquering Israelites. Thus we are informed that

- The children of Lot dispossessed the Emim

- The children of Esau dispossessed the Horites

- The children of Ammon dispossessed the Zamzummim

This theme of a divinely sanctioned dispossession—an ancient literary topos in and of itself—prepares the reader to “accept” the Israelites forthcoming bloody dispossession of the indigenous Canaanites. In other words, the Deuteronomist created precedents upon which the Israelite invasion of Canaan was to be understood.

This theme of a divinely sanctioned dispossession—an ancient literary topos in and of itself—prepares the reader to “accept” the Israelites forthcoming bloody dispossession of the indigenous Canaanites. In other words, the Deuteronomist created precedents upon which the Israelite invasion of Canaan was to be understood.

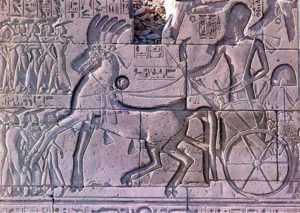

Of course there were other and earlier literary precedents. The Moabite stele, a 9th century engraved text, speaks of the god Chemosh’s commandment for the Moabites to dispossess the indigenous from the land of Moab since he gave this land to its people. Sound familiar? And the epic tale of Aeneas in Virgil’s Aeneid, describes the divinely-ordained dispossession of the indigenous peoples of Italy so that the Romans could take their divinely-promised land.

And we could assume that the Babylonians, Egyptians, and Sumerians all had similar stories of dispossession and the “rightful” possession of lands promised to them by their gods. After all, stories such as these were how ancient civilizations legitimated the ownership of their land vis-à-vis other claimants.

In the end, the Deuteronomist’s argument or “historical” demonstration as to why the Israelites were justified in conquering and taking the land of Canaan was that not only was it promised to them by their god (a theme going back to the earliest textual traditions), but more specifically it was allotted to the Israelites in the context of a larger “divine plan”: As the children of Lot had dispossessed the Emim by divine authority, and the children of Esau had dispossessed the Horites by divine decree, and the children of Ammon had dispossessed the Zamzummim by divine authority, so too the children of Jacob were now to dispossess the indigenous Canaanites by divine authority and earlier precedent!

Such was the power of ancient texts! And as modern readers of the literary lore that the ancient world has bequeathed to us, it is our responsibility to understand the literary conventions they employed and how they functioned in the historical contexts in which they were created—not to ignorantly and disingenuously believe these ancient literary topoi!

What’s interesting here is that it is Yahweh who gives territory to Moab, as opposed to the presumably earlier tradition in Judges in which Chemosh does it.

Do scholars generally believe the portion of Deuteronomy before the actual law code was written around the time of Josiah?

Hi Robert, yes exactly. In fact I am presently finishing the next entry which deals with Chemosh vs Yahweh vis-a-vis the granting of Moabite territory.

I’ve heard arguments that this dispossession of indigenous peoples theme might be part and parcel to Josiah’s reforms, in that they (1) present more amicable relationships between Israel and Edom for instance wherein the Israelites are portrayed as being able to conquer Edom (which would have been historical fact after Edom was destroyed by the Assyrians) but are beckoned not to because Yahweh has declared the land of Edom to the children of Lot; and (2) coincide with Josiah’s military ambitions to retake land after the Assyrians retreated from the area, in an attempt to restore Davidic borders. If this is so, then the dispossession theme above clearly sets out the precedent for retaking northern Moab.

See also 2 Chronicles 20:10.

Delusional lying retarded nigger loving clown, kill yourself ugly pedo vermin nobody likes you.