And the days that we went from Kadesh-barnea until we crossed the wadi Zered were 38 years, until the end of the generation (the men of war) from the camp as Yahweh swore to them. (Deut 2:14)

We have already thoroughly looked at the contradictory traditions preserved in the Torah concerning Kadesh

- Contradiction #260. Where was Kadesh: in the Wilderness of Paran OR Zin?

- Contradiction #261. When did the Israelites arrive at Kadesh: at the beginning of the wilderness period OR in the 40th year?

- Contradiction #274. When do the Israelites leave Kadesh-Hor and travel toward the Red Sea: in the 2nd year after the Exodus OR in the 40th year?

- Contradiction #279. How long is the journey from Kadesh to the Wadi Zered: months OR 38 years?

- Contradiction #332. Do the Israelites travel from Hazeroth to Rithmah OR to Kadesh in the Wilderness of Paran?

- Contradiction #333. When do the Israelites arrive in Kadesh: in the 2nd year OR the 40th?

- Contradiction #334. How many times did the Israelites arrive at Kadesh: once OR twice?

- Contradiction #335. Where were the Israelites from the 2nd to 40th year of the wilderness period: traveling southward from Kadesh toward the Gulf of Elath, then northward back to Kadesh OR traveling northward from Sinai to the Gulf of Elath OR traveling southward, encamping around Mount Seir, and then traveling through Edom?

- Contradiction #338. The Israelites stop at Ezion-Geber just before arriving at Kadesh OR after Kadesh?

And those concerning when and where the first generation of the exodus men were killed off.

- Contradiction #277. Who are the “us” of Num 21:5: the 1st generation Israelites OR the 2nd?

- Contradiction #280. Where are the 1st generation Israelites killed off: in the Wilderness of Paran OR Paran plus Transjordan OR during the trek southward to the Red Sea and northward around Edom?

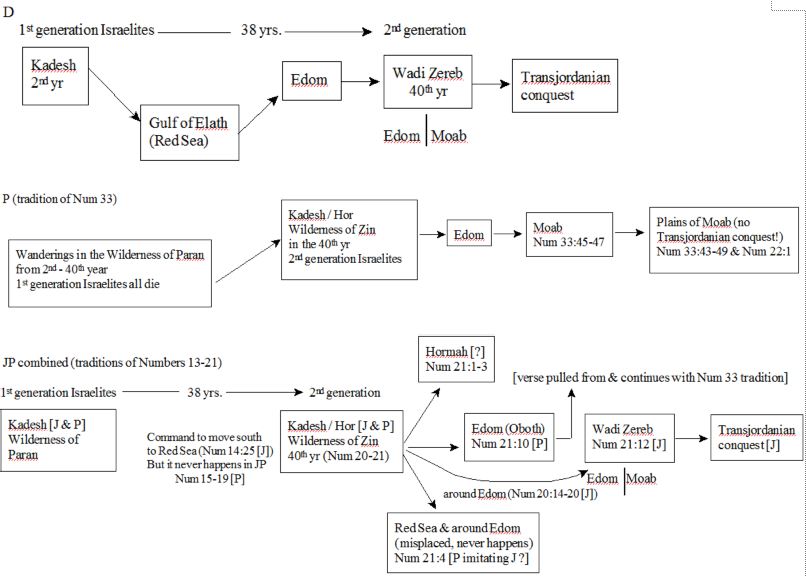

I even created a visual of these competing traditions—the Deuteronomic, Priestly, and Yahwist— to help see how they differed and how they were combined by later redactors.

What I’d like to discuss in this post is a contradiction internal to the book of Deuteronomy and which most likely reflects various Deuteronomic traditions. Except for Deuteronomy 2:14 cited above (I think there’s a second verse somewhere but I can’t recall where), the Deuteronomic tradition does not seem to recognize the extermination of the first generation (the exodus generation) of Israelites tradition. That is to say, and as we shall see, time and time again Deuteronomy’s Moses seems to identify those Israelites assembled before Moses on the plains of Moab in the 11th month of the 40th year of the Wilderness campaign as the first generation of Israelites who left Egypt and witnessed the Horeb revelation!

“And I commanded you at that time. . .”

One noticeable peculiarity about Moses’ renarrations which becomes even more pronounced in his retelling of the Horeb revelation was how he was addressing the people on the plains of Moab. We have already seen in Deuteronomy 1-3 that when Moses renarrates the past events of the Wilderness period he speaks to those assembled before him as if they were present for these events: “I said to you at that time”; “and you answered and said to me”; “and you came to me”; and “I commanded you at that time.” This becomes even more pronounced in his retelling of the Horeb revelation in Deuteronomy 4-5. This is what Moses says to those assembled before him:

- “the day that you stood in front of Yahweh your God at Horeb”

- “you came forward and you stood below the mountain”

- “Yahweh spoke to you”

- “you heard his words”; “he had you hear his voice”

- “you heard the sound of words but perceived no shape”

- “he told you his covenant that he commanded you to do”

- “he brought you out in front of him from Egypt”

- “you saw with your own eyes the signs and portents, the great deeds that Yahweh did at Egypt.”

The “you” that Moses is addressing here in the 40th year on the plains of Moab are spoken of as if they were present at Horeb and witnessed Yahweh’s revelation! This speaks against the extermination tradition whereby all but Caleb and Joshua have long perished. According to this tradition, the “you” to whom Moses addresses and claims that he said certain things to in the past and who heard Yahweh at Horeb are not those who are assembled before him on the plains of Moab. For these are the second generation of Israelites, none of whom, again save Caleb and Joshua, witnessed the Horeb revelation! The “you” that Moses continuously refers to here have all died! They did not hear Yahweh’s words, nor see Yahweh’s great deeds, nor were they liberated from Egypt under Yahweh’s guidance. So what exactly is the author of Deuteronomy doing by claiming that the “you” of Moses’ addresses are those who witnessed Horeb? But there’s more. . .

This “error” becomes even more egregious in other statements that Moses makes about those assembled before him. For example, Moses claims:

- “Yahweh your god has been with you these 40 years.” (Deut 2:7)

- “Remember the long way that Yahweh your God has led you in the wilderness these past 40 years.” (Deut 8:2);

- “Your cloths did not wear out on you and your feet did not swell these 40 years.” (Deut 8:4)

- “From the day that you left the land of Egypt until you reached this place” (Deut 9:7)

All of these statements imply that the Deuteronomist has forgotten or has consciously suppressed the extermination of the first generation tradition. According to this tradition, it was the first generation of Israelites that experienced these things, and for roughly 38 years. In other words, all of these verses portray a counter-tradition to the more commonly known story of Yahweh killing off the first generation of Israelites, save Caleb and Joshua. Is the author of Deuteronomy (or these parts of Deuteronomy) consciously having his Moses—a literary character—retell this older tradition in a modified and contradictory fashion in order to suppress this tradition? And if so, why?

If we look closely, we notice that the sentences above all seem to express a single theological point that the Deuteronomist himself has created as part of his renarration of Israel’s traditional stories. Furthermore the Deuteronomist authenticates this new retelling by using Moses as his authoritative mouthpiece who is presented as merely “renarrating” this past (for more on this subversive technique see Contradiction #349). The theological point that the Deuteronomist has injected into his version of these stories, carved from the necessities of his own geopolitical context, is that Yahweh blessed and watched over the Israelites (the “you” of Moses’ renarrations) for the whole 40 year Wilderness period. It stresses Yahweh’s love, care, and blessing of Israel, despite the Israelites’ disobedience—another theme emphasized throughout Deuteronomy.

Deuteronomy 2:7 highlights this counter-tradition:

Yahweh your god has blessed you in all your undertakings; he has watched over your wanderings through this great wilderness. Yahweh your god has been with you these 40 years; you have lacked nothing.

Again, the “you” being addressed here on the plains of Moab assumes one homogeneous generation of Israelites, the same generation that left Egypt (Deut 5:34, 5:45, 9:7). In its narrative context, yet another counter-tradition—the passing through Edom not around it (see Contradictions #364-369)—Yahweh’s blessing of this homogeneous generation extends to seeing after their provisions, here food and drink from Edom. The Deuteronomist affirms that this was the very expression of Yahweh’s blessings which were with the Israelites, the “you” of these addresses, in all their 40-year wanderings.

This theological presentation of Yahweh as a caring, loving deity is also intricately related to the Deuteronomist’s Horeb covenant and Moses’ “you” who witnessed the revelation. That is to say, the Deuteronomist recreates the tradition asserting that the “you” assembled before Moses were the same group who heard Yahweh and stood before the mountain. The Deuteronomist highlights their covenantal obligations by reminding them that they witnessed, heard, and agreed to the Horeb covenant. Again the theological argument is that Yahweh has kept his end of the covenant, despite Israel’s disobedience.

It must be stressed that these portraits are nothing more than literary devices to convey a powerful theological message. When the geopolitical landscape shifted near the end of the 8th century and then again in the beginning of the 6th century, bringing Assyrian and Babylonian forces against Israel and Judah respectively, the theology adopted by our biblical scribes—indeed a theology prominent in other ancient Near Eastern texts as well—was that these invasions happened because the Israelites themselves had forsaken Yahweh’s laws. Again this is less an historical description and more a theological interpretation of an historical event after the fact. One staple theological tenet throughout all cultures of the ancient Mediterranean world was that each national deity—whether Yahweh, Marduk, Chemosh, Dagan, etc.—served as a divine symbol of worldly justice. If on the one hand a nation lost its land (the central warning in Deuteronomy), and on the other hand the theological given necessitated that that nation’s deity was just, benevolent, and loving, then the only explanation in theological terms to account for this invasion/loss of land was that the people, despite the god’s loving care for them, brought this event on themselves through their disobedience. This in fact is the Deuteronomist’s central message or warning.

So the text and its counter-tradition also serve as a justification for Yahweh. What blame—again theologically speaking—could be assigned to Yahweh when he in fact blessed and loved even the most disobedient generation of Israelites, the “you” of Moses’ addresses. “You heard his words”; “you stood before the mountain”; and “he told you his covenant that he commanded you to do.” The theological demonstration here puts the blame entirely in the hands of the Israelites.

In conclusion, it would seem that the Deuteronomist constructs a counter-narrative that now has only one single generation, from the Exodus through the Horeb revelation to the plains of Moab (40 years), in order to accentuate Yahweh’s extended blessings to a continually disobedient generation: “from the day that you came out from the land of Egypt until you came to this place, you’ve been rebellious toward Yahweh” (Deut 9:7). We have to acknowledge that many of these biblical narratives were created to respond to and answer specific questions and concerns that arose throughout the monarchy, such as “how could a loving god have let Israel/Judah lose its land?” Deuteronomy is a powerful theological response to these and similar concerns. We also see once again that biblical scribes themselves freely modified Israel’s traditions in order to get across the theological message that they wished to convey to their historical audiences. What these modifications clearly reveal is that even for our biblical scribes what these traditions represented were not historical fact, but pertinent theological messages drafted and reshaped for ever-changing historical contexts.